Fitness to Plead

Test of Fitness to Plead in R v Pritchard

To determine whether a Defendant is fit to plead and fit to stand trial the information gathered during the expert witness psychologist assessment must be analysed in the context of the fitness to plead and fitness to stand trial test developed from the case of R v Prichard (1836) 7 C. & P. The test has developed over the years but can be stated as follows:

Does the Defendant Understand the Nature of the Offence?

Part of the assessment of fitness to plead is to test whether an individual understands the nature of the charges they face.

Is the Defendant Able to Comprehend the Evidence?

Defendants may have significant literacy and mental health problems. However, they may be still fit to plead with an intermediary to break the evidence down into a digestible form.

Is the Defendant able to Provide Advice to His or Her Legal Team?

Our expert psychologist evaluates whether a defendant can provide a coherent explanation of events. A defendant may be fit to plead if jury would be able to make adequate sense of the defendant’s evidence.

Additional time and additional support may need to be provided when a defendant is giving his evidence in court.

Typically, our expert psychologists consider whether there are any no apparent signs of delusions or hallucinations. If a defendant can instruct his legal advisers, even with considerable assistance they may be fit to plead.

Is the Defendant able to Understand the Course of Proceedings, So as to Make a Proper Defence?

Connected with this, under the Pritchard criteria, is the defendant’s ability to make a proper defence. Whether or not his version of events is accepted is an issue for the jury to determine.

Does the Defendant Understands the Advice, He or She is Being Given?

If the defendant is able to understand the advice and understand the information necessary to consider that advice properly, they are likely to be fit to plead.

Does the Defendant Understand the Legal Process?

Finally, one must as if the defendant understands the legal process. This means do they understand what the function of a judge is and the judge’s role? If the defendant also understands the role of the prosecution and defence barrister they are likely to be fit to plead and fit to stand trial.

Find Out More About Fitness to Plead and Fitness to Stand Trial

Mental Health Law

Mental Health and the Law

There is a strong relationship between mental health and the law, as far as the rights of people with mental illness is concerned the World Health Organisation outline 10 basic principles that should protect the rights of people with mental illness:

Mental Health Care Law: 10 Basic Principles - World Health Organisation

- The promotion of mental health and prevention of mental disorders.

- Access to basic mental health care.

- Mental health assessments in accordance with internationally accepted principles.

- Provision of the least restrictive type of mental health care

- Self-determination

- Right to be assisted in the exercise of self-determination

- Availability of review procedure

- Automatic periodical review mechanism

- There must be a qualified decision-maker to detain the person

- Respect for the rule of law.

Psychology and the Law

Expert Psychologists who work with individuals who have mental illnesses frequently have two provide expert opinion for the prosecution and defence in criminal cases.

Mental health law includes areas such as the insanity plea, fitness to stand trial and testamentary capacity. Mental health law is also concerned with establishing mens rea and culpability, and compulsory detention.

The intersection between mental health and the law is further developing in the area of forensic evaluation of children and adolescents in child custody, its application to delinquency, maltreatment, personal injury and court-ordered evaluations.

The Mental Health Act 1983

How is Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983 Used?

Section 2 of the Mental Health Act provides the ability of mental health professionals to detain and treat people under the Mental Health Act When they are too unwell to care for or make decisions for themselves. The purpose of Section 2 is to ask the patient to come into the hospital for an assessment to determine whether they have a severe end enduring mental illness. Their detention is in the interest of their own health and safety or the protection of other people. Admission under Section 2 normally lasts for 28 days.

How is Section 3 of the Mental Health Act 1983 Used?

A Section 3 of the Mental Health Act is commonly known as a Treatment Order. This means the patient is compulsorily treated in hospital when certain conditions are met. These are that the individual is suffering from a mental disorder which is of such a degree that warrants the person being compulsorily detained in hospital. There must be a risk to the person or other people. The other conditions are, the treatment cannot be given without the Section 3 being in place, and there must be appropriate treatment available. Detention under Section 3 of the MHA can last up to 6 months.

What Does it Mean to be Sectioned Under the Mental Health Act?

ASD Assessment

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

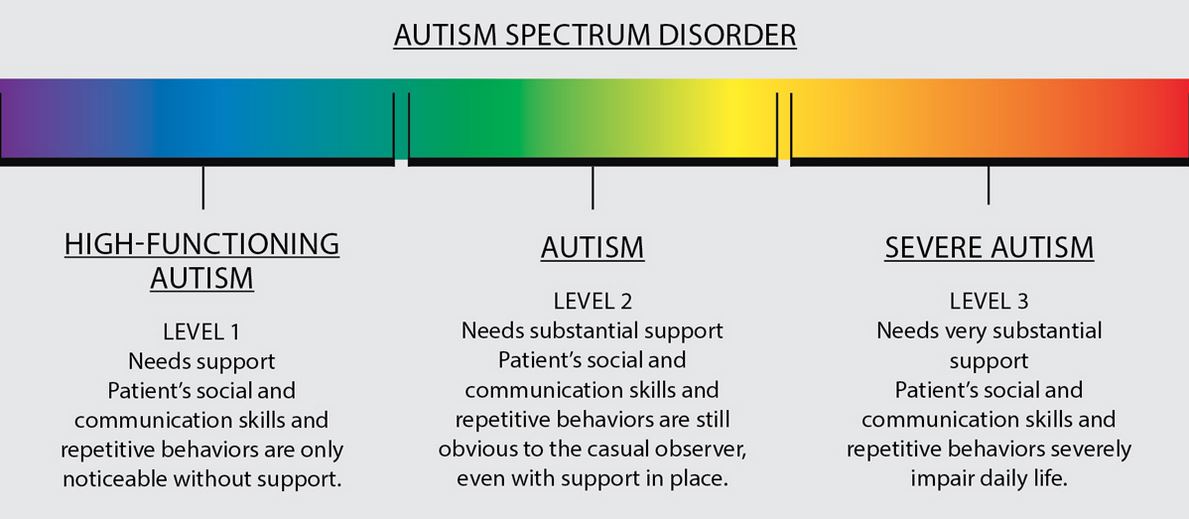

People with autism exhibit the severity of autistic symptoms on a spectrum. The lowest level of the autism spectrum is Level 1 (high functioning autism sometimes called Asperger Syndrome). At the opposite end of the spectrum are individuals at Level 3, these individuals require substantial support.

Figure 1: Autism Spectrum

Autism Symptoms

ASD Assessment

The symptoms of autism displayed may vary according to age, intelligence and whether the individual can speak or not. The key characteristics in the ASD assessment process are summarised below using the framework developed in the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Second Edition). This framework is closely aligned to the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (Fifth Edition) (DSM-5).

Please note that autism can often cooccur with other conditions such as ADHD, dyspraxia, dyslexia, learning disabilities and anxiety.

A. Autistic Language and Communication

Speech Abnormalities

Some people with ASD have speech that has little variation in pitch and tone, rather flat or exaggerated intonation. Sometimes it can be speech that is somewhat unusual or slow or jerky. At the opposite end of the spectrum are individuals with phase speech which is inadequate in complexity or frequency. Some individuals with autism do not speak at all.

Repetition

My individuals with ASD show immediate repetition of the last statement or series of statements given by others.

Stereotyped/Idiosyncratic Use of Words or Phrases

People with ASD range from those who use words or phrases which tend to be more repetitive than most. At the other end of the spectrum are individuals who occasionally use stereotyped words.

Conversation

Individuals with ASD range from those who speech include some spontaneous elaboration of responses to those with little spontaneous communicative speech.

Pointing

Some people with autism use pointing to reference objects and express interest, they do so without coordinated gaze or vocalisation.

Descriptive Gestures

Many individuals with autism use some descriptive gestures to represent an event such as brushing one’s teeth or combing one’s hair. Others use very limited conventional or descriptive gestures.

Offers Information

An individual with ASD may spontaneously offer information at one end of the spectrum. At the other end of the ASD spectrum, an individual may rarely offer information except about their circumscribed interests.

Asks for Information

At one end of the ASD spectrum, individuals may occasionally ask for information. At the other end, the individual will rarely or never ask others about feelings or experiences.

Reports Events

Some people with autism can report specific nonroutine events. At the opposite end of the spectrum, some individuals provide inconsistent or insufficient responses to even specific probes.

Conversation

Individuals vary from those who can engage in dialogue to those who have little spontaneous communicative speech.

Descriptive Gestures

At one extreme some individuals make spontaneous use of several descriptive gestures. At the other end, there is very limited spontaneous use of conventional, instrumental, informal or descriptive gestures.

Emphatic or Emotional Gestures

There is a spectrum of abilities with some people able to show a variety of appropriate and emphatic and emotional gestures that are integrated to speech. At the other end of the spectrum, there are those that show no or a very limited emphatic or emotional gestures.

AUTISM SPECTURM DISORDER

B. Reciprocal Social Interaction

Some Individuals Display Poor Eye Contact

Some individuals with ASD display poor eye contact to modulate or terminate social interactions.

Ability to Direct Facial Expressions Appropriately

Some individuals with autism do not direct their facial expressions to other people when communicating appropriately.

Ability to Show Pleasure and Shared Enjoyment and Interaction

Some individuals with ASD can show pleasure during more than one activity. Some people with autism may have little or no expressed pleasure in interactions.

Ability to Communicate Own Effect

Although some autistic individuals can communicate a range of emotions, others have hardly any or no communication of what they are feeling or have felt.

Ability to Link Speech to Non-Verbal Communication

At one end of the spectrum, individuals moderate their non-verbal gestures in line with their speech. At the other end of the spectrum there is some avoidance of eye contact, or in extreme cases, individuals are unable to speak or make minimal or no use of gesture and facial expression.

Ability to Communicate Feelings and Emotions Using Words

While some individuals are able to communicate many emotions, the feelings they have felt ―others exhibit hardly any ability to communicate the feelings and emotions verbally and nonverbally.

Ability to Understand of The Emotions of Others and Show Empathy to Others

Although many individuals with autism can understand and label or respond to the emotions of others; some individuals have no or minimal ability to identify, communicate and understand the emotions of others.

Ability to Show Insight into Social Situations and Relationships

Some individuals with autism show no or limited insight into typical social relationships. At the other end of the autistic spectrum, some individuals show insight into the nature of many typical social relationships.

Ability to Show Responsibility for His or Her Own Actions

At one end of the autistic spectrum are individuals who are responsible for many of their own actions across a variety of contacts which include daily living, work school and money et cetera. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who have a restricted sense of responsibility for their actions as would the appropriate to their level of development and age.

Quality of Attempts to Initiate Social Interaction

At one end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who use verbal and non-verbal methods to communicate social overtures appropriately. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who cannot engage in social overtures of any kind.

Frequency of Attempts to Get an Maintain Attention of Others

Although some individuals make frequent attempts to maintain the attention of others and direct their attention, others show an unusually frequent or excessive demand for attention.

Quality of Social Responses

While some individuals display a diversity of appropriate responses that change according to the immediate situation. However, others have minimal or inappropriate responses to the social context.

Frequency of Reciprocal Social Communication

Autistic individuals vary from those who make extensive use of verbal or non-verbal behaviours for social interchange to those that engage in little or no communication.

C. Imagination

Imagination/Creativity

Some individuals with autism show no creative or inventive actions. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who display numerous creative, spontaneous responses in activities and communication.

D. Stereotyped Behaviours and Restricted Interests

Unusual Sensory Interest in Play Material

Some individuals with ASD exhibit a pronounced unusual sensory interest while others show no unusual sensory interests or sensory seeking behaviours.

Hand to Finger and Other Complex Mechanisms

Some individuals with ASD display no hand to finger or other complex mechanisms such as repetitive clapping. At the other end of the spectrum, there are individuals who frequently exhibit such behaviours.

Self-injury

Some individuals with ASD engage in aggressive acts to harm themselves, these acts include headbanging, pulling out their own hair, biting themselves or slapping their own faces. Other individuals with ASD do not engage in this type of behaviour.

Disproportionate Interest or Reference to Specific Topics or Repetitive Behaviours [h3]

Some individuals with ASD display a marked preoccupation with interests or behaviours which interfere with their day-to-day activities. For example, a type of car. Other individuals with ASD display no excessive interests.

Rituals and Compulsions

Some individuals show obvious activities or verbal routines which must be discharged in full or in line with a sequence which is not part of a task. However, others may have one or several activities or routines which they have to complete in a specific way. They will become anxious if this activity is disrupted.

Other Abnormal Behaviours

Although some individuals can sit still appropriately, other individuals with ASD may have difficulty sitting still and may be overactive. Some individuals with autism, however, may be underactive.

Autism Meltdowns, Aggression and Disruption

Many people with autism display no destructive or aggressive behaviour. However, some people with ASD may talk loudly, they may have significant temper tantrums. Such tantrums frequently occur when there is a change of routine or change of environment.

Anxiety

Whilst many individuals with ASD show no marked signs of anxiety, others show significant anxiety in their day-to-day interaction.

ASD CHECKLIST - HOW MUCH DO YOU REALLY KNOW ABOUT AUTISM?

Find Out More About Autism

NHS Choices – Autism Spectrum Disorder

What is Autism?

What is Autism? Scottish Autism

Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome

Everything You Need to Know About Autism

Autism

Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment

Autism and The Law

People with ASD in the criminal justice system are affected as victims, witnesses and defendants. It is important that defendants with ASD are not unnecessarily criminalised because of their condition. The Youth Justice Centre (2018) recommend that it is important that both victims and defendants are supported to give best evidence at the police station and at court.

Because many people with autism are often quite vulnerable, there is a need for prosecutors to draw this to the attention of judges when sentencing perpetrators of crimes against victims with ASD.

Autism and Criminal Defence

Some individuals with autism may find it difficult to answer even the most straightforward questions asked by the police. Additionally, some young children with autism who self-harm may unwittingly be assumed to be victims of child abuse.

A person with autism might:

- Be overwhelmed by police presence;

- Fear a person in uniform;

- React with fight or flight;

- Not respond to “stop” or other commands; and

- Not respond with his or her name or other verbal commands

- May avoid eye contact.

Mogavero (2016) found that too many individuals with ASD are enter the criminal justice system due to inappropriate sexual behaviour.

Judges have discretion when sentencing, and it is important to point out that a custodial sentence may have a more devastating effect for an individual with autism than someone without the condition.

AUTISM AND CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY

LEARN MORE ABOUT AUTISM AND THE LAW

Autism and the Criminal Justice System

Autism Information for Law Enforcement

Autism and the Criminal Justice System

Autism and Oughtisms

Autism – Youth Justice Legal Centre

Autism, Sexual Offending, and the Criminal Justice System

Autism and Offending Behaviour: Needs and Services

Understanding offenders with autism-spectrum disorders: what can forensic services do?: Commentary on…..Asperger Syndrome and Criminal Behaviour

Autism and Disability Discrimination

Autism and Child Contact

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)

Pathological Demand Avoidance in Adults

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

People with Pathological Demand Avoidance or PDA are driven to avoid demands due to their high anxiety levels when they feel that they are not in control.

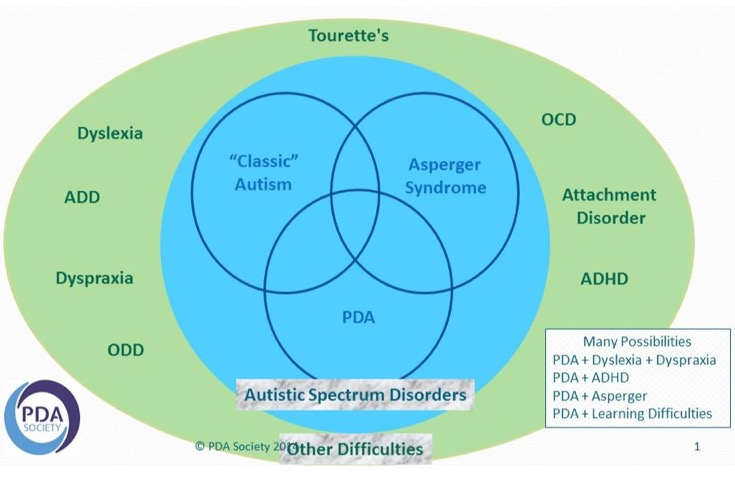

PDA is increasingly recognised as being part of the autism spectrum. Some psychologists refer to it as a diagnostic profile or sub-type within autism. Individuals with PDA share difficulties with others on the autism spectrum in terms of social aspects of interaction and communication, together with some repetitive behaviour patterns. However, people with PDA often seem to have better social understanding than others on the spectrum

In individuals with PDA, their avoidance is clinically-significant in its extent and extreme nature. Children and adults with PDA can also mask their difficulties, and their behaviour can vary between settings.

PDA is a relatively new diagnosis it is frequently confused with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) as a diagnosis. PDA as shown in the diagram below from the PDA Society (www.pdasociety.org.uk) PDA falls within the circle of Autistic Spectrum Disorders, whereas ODD does not. There other conditions with frequently cooccur with autism in the green circle.

Figure 1: Pathological Demand Avoidance and its Interplay with Autism

Please note that Asperger Syndrome is now referred to as High Functioning Autism (HFA), although there is still some dispute that they are separate conditions.

There is overlap between most of these diagnoses. The term 'can't help won't' is often used to describe PDA.

PDA Not Yet Recognised in the DSM-5 and ICD-10

Many people are diagnosed with PDA as a condition in its own right. Presumably, this is because they do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum disorder ASD. The problem with this approach is that:▪ PDA is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - fifth edition (DSM-5)

▪ PDA is not included in the International Classification of Diseases - 10th Edition (ICD-10)

Consequently, if the condition does not appear in the leading diagnostic manuals for psychological conditions some schools and educational institutions may find it difficult to provide support. Many argue that every individual with PDA is autistic.

PDA as a Form of Autism Spectrum Disorder

It is becoming more common for people to receive a diagnosis of ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) characterised by extreme demand avoidance.’ Alternatives ways of putting the diagnosis are:

ASD with a PDA profile;

ASD sub-type PDA; or

Atypical autism with demand avoidant tendencies.

Learn more about the key Characteristics of Pathological Demand Avoidance

6 Main Characteristics Pathological Demand Avoidance Are:

Resisting and avoiding the ordinary demands of life;

Using social strategies as part of the avoidance;

Appearing sociable on the surface but lacking depth in their understanding;

Excessive mood swings and impulsivity;

Being comfortable in role play and pretence, sometimes to an extreme extent and often in a controlling fashion; and

Obsessive’ behaviour that is often focused on other people, which can make relationships very tricky.

Individuals with PDA have Many Positive Characteristics

One should not lose sight of the fact that individuals with PDA can be quite positive and have many strengths. They can interact well socially and can be quite talkative. They are said to have charm and can be warm and affectionate. Their need to take control means that they are often seen as quite determined. They can have a rich imagination and are frequently described as creative and passionate.

8 Top Tips on How to Support Individuals with Pathological Demand Avoidance

Pathological Demand Avoidance Treatment

1. Flexibility

Always make sure that your day activities are flexible, the the individual with PDA child might not want to do them in a particular order they might want to do it in a completely different order. Allow that flexibility and you will find that the individual with PDA will be able to cope with the anxieties of the day a lot easier.

2. Control.

People with PDA need to feel so they are in control like autism, and other ASDs anxiety rules the day for them if they do not feel in control of a situation the sense of anxiety rises and then they feel panicky and fearsome of what is going to happen; particularly when it comes to change for PDA individual the fear of not being in control generates a resistance to what if the change or a request you might want them to do something they might not be able to do or not want to do it because they might get it wrong.

3. Ease Anxiety.

If changes needed, then talk the PDA individual through it you might want to talk to them you might want to write it down in steps like bullet points or you could use images or pictures either way show the PDA individual that there is a beginning a middle and the end of a request or activity you want them to carry out; this will ease the anxiety for the individual

4. Unravel the Fear

PDA individuals often see the worst in every situation they will always think of the worst thing that could possibly happen; reassure the PDA individual that there is nothing to worry about - do not be confrontational.

5. Building up Self Confidence

A lot of PDA individuals have a problem with self-esteem and confidence they think that if they do whatever it is they are being asked to do they are not going to do it properly; it might be that they feel they will be laughed at. They might feel embarrassed. There is a huge amount of anxiety that is behind these inner fears the best thing to do is boost up PDA individual’s confidence tell them exactly what they get right, tell them what they are good at.

6. Make the change outcome beneficial

Help the person with PDA see that the change out is beneficial to them, and not to you. The key here is to make them feel that they are making the decision themselves, make them think that actually the decision is their decision. Always make the outcome look beneficial to them and not to you.

7. Provide a Responsibility

We know that people with PDA love to be in control of their own world given the responsibility to do something to help themselves this will make them feel as though they are completely in control of their being and their body and, therefore, the outcome. The secret to it is careful wording in the request do not bark an order at them but suggest a way of doing something and add the element of responsibility into that request so they feel as though they are doing something for themselves.

8. Set boundaries

People with PDA need to know there will be a beginning a middle and an end. Help them to think what it will be like to achieve the end result. Provide them with a sense of responsibility.

Learn More About Pathological Avoidance Syndrome

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

Pathological Demand Avoidance

Pathological Demand Avoidance – One Family's Story

Pathological Demand Avoidance: Behavioural Strategies