George Floyd Trauma

SOCIAL MEDIA IMAGES OF POLICE KILLINGS OF BLACK PEOPLE AND PSYCHOLOGICAL TRAUMA

Images of Black people being killed or brutalised by the police have a special meaning for Black people. These images trigger anxiety and memories of police brutality in victims and their families.

Many Black people have experienced brutality by the police directly or know someone who has experienced it.

BBC News Interview with Dr Bernard Horsford on the Psychological Trauma of Witnessing Police Violence on Social Media

Anxiety and trauma can be caused because many Black people will think they may also be subject to violence by the police.

The mental health problems caused by witnessing racist violence has been recognised by both the American Psychiatric Association ― who state that psychological trauma including PTSD has been caused by seeing images of Black people suffering abuse by the police.

There is a similar statement published by the American Psychological Association (APA). The APA statement deals with the ongoing psychological trauma caused to Black communities by seeing people repeatedly killed by the police. The President of the American Psychological Association said we are living in a racism pandemic.

The research is clear that repeated viewing of images of violence by the police and authorities can lead to acute stress symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and depression. Tynes et al. (2019) found viewing images of police killings leads to worse mental health outcomes.

Witnessing racist incidents harms mental health ― when we see these distressing images, the trauma can lead to anxiety disorders or exacerbate conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Images of Black people killed by the police may stay in the mind of those who view them for many months.

There is a strong sense of community and shared experience of discrimination in Black communities, so these images have a much stronger meaning for Black people. Other communities have also been outraged by these incidents.

Unfortunately, there were many incidents of Black people being killed by the police before George Floyd was murdered. For example:

- Ahmed Arbury (was shot by ex-police officers when he was out jogging);

- Breonna Taylor (shot and killed at home in error when the police raided the wrong house);

- Eric Garner (killed by the police in a hold similar to George Floyd where he could not breathe);

- Rodney King (was beaten by the police, the incident was filmed but the police acquitted); and

- Philando Castile, (shot by police while driving).

In the UK there have been deaths of Black people following police intervention which have sparked outrage by Black communities such as Sean Rigg, Joy Gardner, Mark Duggan, Edson da Costa, and Rashan Charles.

African American’s are twice as likely to be shot by the police as White people. Black people are more likely to have force used against them (particularly Tasers). A Home Office report in 2018 found that Black people experienced 12% of incidents of police force despite being made up of only 3.3% of the population in England and Wales.

History has told us that when communities see these injustices this frequently leads to civil unrest. Incidents of excessive and unlawful police violence led to unrest in the 1960s in the 1980s and 1990s in the USA.

It was also said that the Brixton uprising in 1981 in the UK was triggered by heavy-handed policing under the stop and search laws. A young person was said to have died because of police brutality.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

For the Authorities:

For the Authorities:

Act swiftly against deaths of Black people ― take the most serious action against the perpetrators. Prosecute and ensure that there is robust evidence to secure convictions. This will help the community see that justice is being done.

Follow the rules that the police are employed to enforce. It is hard to get respect when police do not follow the rules and kill Black people.

Ensure greater accountability; there needs to be more Black people in positions of power to drive change and ensure equality, diversity and inclusion.

For Black People Who See Images of Police Violence:

Seek professional help from psychologists or therapists with an in-depth understanding of Black communities and how racism and discrimination affect Black people.

If it can be shown that an incident that they witnessed caused a recognised psychological condition, then seek legal advice to determine if they have sufficient evidence to make a legal claim for personal injury.

Seek community support and talk about your experiences; this can be very therapeutic.

Try strategies which support distraction from the worry. Take physical exercise and focus on positive thinking.

Use online mental health resources (for example, on our website) on cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling and online mental health diagnosis.

Think positively and use your experience as a positive driver for change.

Work with community groups to address change.

Revisit the place of your trauma to try to reduce the fear associated with the place.

Do not keep on looking at the images of police violence which cause you distress.

Carry evidence so you can record any instances of police violence, most of the cases will be unsuccessful without photographic evidence or evidence of other people.

Find out More About Community Psychological Trauma and Police Violence

- George Floyd death: Trump threatens to send in army

- What happened on the night of George Floyd's arrest

20210101180001

Medical Neglience

What Is Medical Negligence?

What is medical negligence, and how might clinical negligence impact on our psychological well-being? An example of medical negligence is where a healthcare professional provides you with substandard treatment that is so inadequate that no other competent healthcare professional would have provided the procedure in this way.

Alternatively, medical negligence can arise from a failure to provide any treatment at all in the circumstances when another healthcare professional would have done so.

Medical negligence typically happens when the individual suffers injury as a result of is inadequate treatment or failure to provide treatment.

As psychologists, we work with solicitors and barristers to objectively assess the psychological injury that an individual has suffered as a result of medical negligence.

One must remember that not all errors are clinical negligence, and not all poor outcomes of treatment are a result of medical negligence.

Find Out More About Medical Negligence

Suggestibility Assessments

How Does Suggestibility, Conformity, Obedience and Compliance Result in False Confessions or Illegal Behaviour?

"Suggestibility has been shown by psychologists to cause false confessions. Psychologists have demonstrated conformity, obedience and compliance can cause illegal behaviour. An assessment by an expert psychologist of a defendant who is considered to be suggestible or compliant is a crucial part of constructing a defence that ensures there are no miscarriages of justice."

What is a False Confession?

A false confession occurs when a defendant, admits to a crime that they did not commit. The psychological process of false confessions is complex. However, the research reviewed by our expert psychologists and their practical experience of working with defendants and in the criminal justice system demonstrates that some individuals are psychologically more likely to confess to crimes than others. There are often psychological factors which can be objectively measured in some defendants which show a propensity to make false confessions to crimes that they did not commit.

There are several reasons why an individual might make a false confession, for instance, a defendant may make a false confession to attempt to mitigate the possibility of receiving a harsher sentence when, although they are innocent, the factual evidence does not support their innocence. Sometimes, defendants may make a false confession to protect a friend or relative who committed the crime. In other instances, a defendant may confess to something they did not do because they are suffering from a mental disorder. Defendants may make a false confession in response to a bribe from a third party. False confessions also frequently occur when individuals are easily led, have low IQ or personality factors resulting in them feeling pressurised into admitting to offences they have not committed.

How Does Offender Suggestibility Impact on the Quality of Evidence?

"In legal psychology, suggestibility relates to the phenomenon that is found when a subject under interrogation yields to leading questions when pressure is applied and shifts their answers when interrogative pressure is applied. Put another way; the psychologically suggestible suspect admits facts which are incorrect under pressure. This is often called interrogative suggestibility. For lawyers, the concept of suggestibility is vital because it is critical that the court has robust evidence to show the defendant’s guilt or innocence. Suggestible defendants may, therefore, admit offences that they did not commit because of their suggestibility, the quality of their evidence under cross-examination in court is likely to be reduced, and they are unlikely to come up to proof."

Suggestible witnesses often possess one or more of the following characteristics:

- A low IQ or learning disability;

- Submissive personality;

- Conforming personality;

- Are suffering from a mental illness;

- Are juveniles; and

- A low Mental age

The leading measure of suggestibility is a psychological test called the Gudjonsson Suggestibility Scale (GSS). Gudjonsson Suggestibility Scale Download. Elevated scores on the GSS are correlated with suspects who are likely to make false confessions under cross-examination or interrogation.

Advanced Assessments’ expert witness psychologists use the GSS in combination with other psychological tests, such as personality tests, IQ test as well as a structured clinical interview, the Wechsler Memory Scale, the Test of Memory and Learning, observations and content analysis of the relevant documents to objectively assess whether the suspect is suggestible. By using this multi-method approach, our expert psychologists can gather robust and reliable objective data to clearly show whether a subject is, in fact, suggestible. In this way, our expert psychologists can use reliable and valid evaluations of suggestibility that rule out attempts to fake suggestibility and meet the very high standards required under the expert’s overriding duty to the court.

Why is Police Suspect Suggestibility Important in Legal Proceedings?

Our expert psychologists assess police suspect suggestibility to establish whether a defendant is likely to produce false low-quality evidence and false accounts when interrogated by the police or cross-examined in court. The GSS is sometimes used along with other psychological tests to determine whether a defendant is fit to plead and fit to stand trial.

An assessment of suggestibility is also essential when determining whether eyewitness evidence is reliable in criminal, civil, employment tribunal, personal injury and other legal proceedings.

How Does Conformity, Compliance and Obedience Differ from Suggestibility?

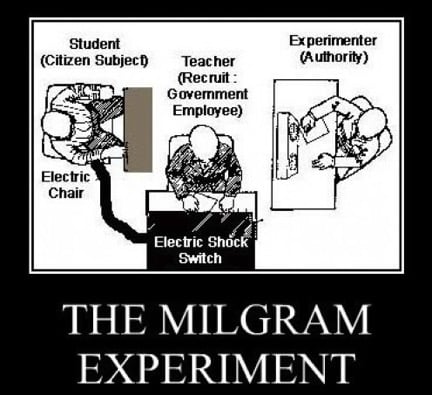

Conformity, compliance and obedience are different to the psychological concept of suggestibility. The concept of obedience and conformity can explain why defendant’s commit offences under the orders of individuals who they regard to be authority figures. The psychological phenomenon of obedience was demonstrated by Stanley Milgram of Stanford University. Milgram's research showed that ordinary people would obey authority figures and administer lethal doses of electric shocks, which would apparently kill the person on the receiving end. This work was ultimately used to explain the war crimes committed during the Second World War.

The concept of conformity, on the other hand, is used to explain the psychological process where individuals will change their behaviour and views to fit in with the dominant view of the group, to such an extent that they may give factually wrong information because of group pressure. The leading study was carried out by Solomon Asch, who demonstrated how susceptible individuals are to group pressure.

Find Out More About the Psychology of Suggestibility, Conformity and False Confessions

Suggestibility

Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

False Confessions

Parental Alienation Syndrome & Family Law

What is Parental Alienation Syndrome?

"Parental alienation is often raised as a reason for children not wanting to see the parent who they do not live with in child contact and residence disputes. The psychological process of parental alienation is said to develop by the parent with care, and therefore with power, directly or indirectly causing the child to show unjustifiable anxiety, disrespect or hostility towards the non-resident parent. The result of the processes is that the child ultimately rejects the non-resident parent, and typically asserts that they are doing this of their own volition. The process is problematic because, in child contact and residence disputes in the United Kingdom, the family courts place the wishes and feelings of the child at the centre of their decision-making. Therefore, when a child says that it does not want to see the non-resident parent, this assertion is likely to be given considerable weight by the courts; unless it can be demonstrated that the child is a victim of parental alienation."

The UK courts often prefer to use the term implacable hostility to describe the symptoms shown by the parent with care when a child has been subject to parental alienation. Some psychologists and psychiatrists use the term pathogenic parenting to describe parental alienation by the parent with care.

It is important to note that the process of parental alienation is hugely damaging to the psychological well-being of the child that has been alienated. A good childcare lawyer will, therefore, direct the expert to consider whether the child has suffered significant harm. If a child has suffered significant emotional (psychological) harm within the meaning of the Children Act 1989, as a result of parental alienation, this can be a strong argument to reverse the current residence or child contact arrangements in favour of the parent that does not have residence or has limited contact with the alienated child. Put another way, many expert psychologists and child care mental health professionals believe that parental alienation is child abuse.

Our expert psychologists have worked with children and young people in several settings and provided advice for parents in child contact disputes.

Why Has it Been So Difficult for a Diagnosis of Parental Alienation to be Accepted in UK Courts?

Our expert psychologists are particularly familiar with the work by Richard Gardner on parental alienation syndrome, a concept that has been recognised by some in the USA but has not generally found acceptance by the family courts in the UK. The concept is controversial. Parental alienation syndrome has not received general acceptance by the courts for two key reasons:

- an alienation syndrome is not a professionally recognised diagnosis; and

- the absence of a reliable clinical-forensic assessment of the alienation syndrome.

"Consequently, parental alienation did not exist as a discrete category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in the American Psychological Association DSM-IV (which is now obsolete). However, this does not mean that such a process does not exist. Our expert psychologists have observed the process in several family settings."

This explains why the assessment of parental alienation does not form part of the formal training of psychologists or psychiatrists. Formal training in the area is, therefore, by self-directed learning and practical experience of dealing with such cases.

How is Parental Alienation Diagnosed?

Dr Craig Childress, one of the leaders in this field, teaches that parental alienation is a two-person diagnosis. Childress believed it is necessitated by the child’s primary diagnosis of a shared psychotic disorder (DSM-IV TR Code 297.3) when the child effectively shares the delusional belief system of the alienating parent.

Central to this model is the view that the alienating parent has a personality disorder with borderline, narcissistic and antisocial features. Emerging from the personality disorder of the alienating parent is an “encapsulated” delusional disorder (a fixed belief system that is impervious to facts, reason or evidence) involving the inadequacy of the targeted parent (often the parent without care). The fixed belief system represents an intransigent psychological re-enactment dynamic of early childhood relationship trauma consistent with the development of personality disorder.

In when the DSM-5 was developed, Dr Childress refined his model it fits with the following DSM-5 diagnosis:

- 309.4 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance and emotions and conduct

- V61.20 Parent-Child Relational Problem

- V61.29 Child Affected by Parental Relationship Distress

- V995.51 Child Psychological Abuse, Confirmed (pathogenic parenting)

Richard Gardener believed that parental alienation syndrome appears mainly in child custody dispute where the child turns massively against the parent without care without reasonable grounds for doing so. This action of the child is a result of the parent with care’s emotionally abusive attempts to incite the child against the non-custodial parent. Gardener believed that where a child’s rejection of the parent is based on some real experience, a diagnosis of parental alienation should not be made.

Find Out More About Parental Alienation

Fitness to Plead

Test of Fitness to Plead in R v Pritchard

To determine whether a Defendant is fit to plead and fit to stand trial the information gathered during the expert witness psychologist assessment must be analysed in the context of the fitness to plead and fitness to stand trial test developed from the case of R v Prichard (1836) 7 C. & P. The test has developed over the years but can be stated as follows:

Does the Defendant Understand the Nature of the Offence?

Part of the assessment of fitness to plead is to test whether an individual understands the nature of the charges they face.

Is the Defendant Able to Comprehend the Evidence?

Defendants may have significant literacy and mental health problems. However, they may be still fit to plead with an intermediary to break the evidence down into a digestible form.

Is the Defendant able to Provide Advice to His or Her Legal Team?

Our expert psychologist evaluates whether a defendant can provide a coherent explanation of events. A defendant may be fit to plead if jury would be able to make adequate sense of the defendant’s evidence.

Additional time and additional support may need to be provided when a defendant is giving his evidence in court.

Typically, our expert psychologists consider whether there are any no apparent signs of delusions or hallucinations. If a defendant can instruct his legal advisers, even with considerable assistance they may be fit to plead.

Is the Defendant able to Understand the Course of Proceedings, So as to Make a Proper Defence?

Connected with this, under the Pritchard criteria, is the defendant’s ability to make a proper defence. Whether or not his version of events is accepted is an issue for the jury to determine.

Does the Defendant Understands the Advice, He or She is Being Given?

If the defendant is able to understand the advice and understand the information necessary to consider that advice properly, they are likely to be fit to plead.

Does the Defendant Understand the Legal Process?

Finally, one must as if the defendant understands the legal process. This means do they understand what the function of a judge is and the judge’s role? If the defendant also understands the role of the prosecution and defence barrister they are likely to be fit to plead and fit to stand trial.

Find Out More About Fitness to Plead and Fitness to Stand Trial

Dyslexia & the Law

Dyslexia

What is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is characterised as a lifelong reading disorder caused by a neurological difference in the brain. People with dyslexia’s intelligence does not match up to their performance in academic areas such as reading, spelling and writing. It is important to get a diagnosis of dyslexia quickly because with the right support people with dyslexia can achieve outstanding results in education, employment and other areas of life. The right support can address the problems often associated with dyslexia.

Dyslexia Diagnosis

Dyslexia can be diagnosed through a series of approved test which are memory, processing speed, ability to reason with words and the ability to reason without words. Our expert psychologist will compare the client’s underlying cognitive ability (as measured by these tests) with their performance on literacy test measuring, reading, spelling, and handwriting. Where the expert psychologist finds the client’s, academic achievement is inconsistent with their underlying ability (IQ) a diagnosis of dyslexia may be made. To read more about dyslexia symptoms click this link

Dyslexia Assessments

Our dyslexia assessment can take up to are completed at the client’s pace, we do not set dictate that the assessment must be completed within three hours. The assessment can be conducted at home or in the Advanced Assessments Assessment Centres. The Dyslexia Diagnostic Assessment will measure reading, writing and spelling, measure handwriting and fine motor skills, and observe the learner’s ability such as speed of processing language, memory and speech. Through this assessment, the client will be formally diagnosed. Must important we will provide strategies and an action plan for the client the reach their full potential.

Find Out More About Dyslexia and the Law

Legislation - British Dyslexia AssociationExpert Witness Psychologists

Expert Witness Psychologists

What is Psychology?

Psychology is the science of mental life. The discipline is of relevance to professionals working in various areas of the legal profession.

How Expert Witness Psychologists Assist in Criminal Proceedings

Expert Witness Psychologists are often called on by criminal law experts to advise on whether an individual needs an intermediary to participate fairly in the proceedings as either a defendant or a witness for the prosecution. Psychologists often indicate whether an individual needs further evaluation to determine whether they are fit to plead. Additionally, psychologists may be able to advise the court whether an individual was culpable of an offence that they have been charged with because of an underlying psychological condition.

Psychologist expert witnesses are often called to give evidence in parole hearings, and advise parole boards whether a prisoner is suitable for parole.

How Expert Witness Psychologists Assist in Employment Tribunal Proceedings

Psychologist expert witnesses also assist in employment tribunal proceedings. They are often called on to advise on whether an assessment selection process or redundancy process was discriminatory. They also advise Employment Tribunal is on whether or not the claimant before the tribunal had a disability within the meaning of the Equality Act 2010. Individuals in the workplace often suffer from a wide range of disabilities including, depression, anxiety, dyslexia, and ADHD. These disabilities are often hidden but in certain situations can adversely affect individuals gaining employment and staying in a job.

How Expert Witness Psychologists Assist in Personal Injury Proceedings

In personal injury proceedings, expert witness psychologists are often called on to assess the cause of psychological trauma, determine how long it will take the claimant to recover. Expert psychologists working in this area frequently carry out neuropsychological assessments of brain injury. In all areas where psychological is carried out expert psychologists will often see to validate the findings by using a range of psychological techniques to detect malingering, and symptom exaggeration.

How Expert Witnesses Psychologists Help In Care Proceedings and in The Family Court

Psychologist expert witnesses are often called upon by social services departments and families in private and public law care proceedings. They carry out assessments of fitness to parent, whether the child subject to the proceedings has been harmed or is likely to be harmed by the parents or the likely disputes that have taken place between the parents. They are frequently asked by both social services departments, fathers and mothers to determine the level of attachment and to advise whether the child has suffered parental alienation (pathogenic parenting).

In family law cases, expert psychologists often carry out risk assessments to determine whether the child would be at risk if there was unsupervised contact unsupervised contact

How Expert Witness Psychologists Assist In Housing Law and Possession Proceedings

Individuals who are subject to possession proceedings, frequently lack the capacity to make a proper defence and conduct their own affairs including issues that might put them at risk of being evicted. Such action can be discriminatory under the Equality Act 2010. Expert psychologists can often advise in these cases, for example where depression or conditions such as hoarding disorder impacts on the ability of the tenant to manage their property.

How Expert Witness Psychologists Help In Education Law

In education cases, expert witness psychologists often assist parents by carrying out assessments to ensure the relevant child has an appropriate Educational and Health Care Plan. Additionally, Expert witness psychologists appear in Educational Needs and Disability Tribunal’s, and also provide evidence in judicial review proceedings when parents challenged the educational provision offered to the child.

Find Out More About Psychologists

Immigration Psychologists

Psychological Assessments of Deportation and Immigration

Deportation may have many adverse psychological effects; it can result in trauma and stigma which is caused by hardship and being unable to maintain contact with key family members.

Many people may be returned to harsh environments where they may be subject to torture and psychological and physical harm.

There is typically psychological stress, depression and anxiety associated with deportations. The trauma also adversely affects academic performance with children often becoming withdrawn after the deportation. Children might start to engage in self-destructive behaviours, inflict self-harm, become distressed, and exhibit other mental health conditions. There may be disturbances in sleeping patterns; some children may become more aggressive. The psychological effects include mistrust, fearfulness and becoming hypervigilant. Children often experience a sense of shame and secrecy.

Individuals who feel targeted may stop participating in community life; they may move away from the support systems that kept their families psychologically healthy.

These negative psychological consequences may continue even after the children are reunited with their families. Family members often must take on jobs to make up for the lost income of the primary breadwinner.

Our expert psychologists can help by assessing families who are subject to immigration proceedings and providing evidence to the tribunal on how deportation may impact on the psychological well-being of those affected by immigration and deportation proceedings.

Immigration Psychological Assessments

Life in the UK Test – Reasonable Adjustments and Exemptions

Dyslexic people may be able to receive reasonable adjustments for The Life in the UK Test. To receive such an adjustment, one would need to provide evidence of your dyslexia. Reasonable adjustments include:

Hundred per cent extra time;

An online test with a reader and scribe who will select the answers as given by the examinee;

A British Sign Language Interpreter;

A session alone with no other candidates;

The use of a coloured overlay on the screen; and

Special equipment such as a larger screen and ergonomic mouse.

If you have a mental health condition, you may be exempt from completing the whole of the Life in the UK Test. Our expert psychologists would need to carry out an assessment to determine whether the candidate has a qualifying mental health condition

Find out More About the Psychology of Deportation

Offender Profiling and Crime Analysis

What is Geographical Offender Profiling?

Geographical profiling is the study of criminal spatial behaviour, the development of decision support tools that incorporate research findings, studies of the effectiveness of these applications and exploration as to how such tools can help the police investigation. There are two fundamental approaches to geographic profiling (a) that individuals have a mental map of the areas and (b) route finding ability.

How Can Geographic Profiling Help the Police?

Geographic profiling:

helps with prioritisation of offenders;

gives guidance on where to seek intelligence;

links crime to a common perpetrator;

predicts where the next crime is likely to take place; and

possibly links the geographical style to an offender.

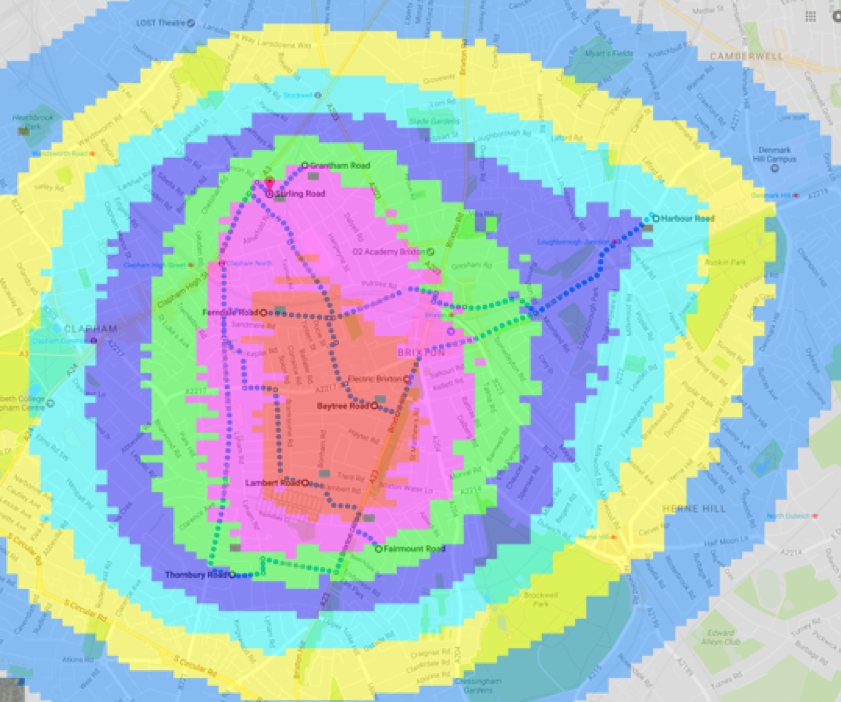

Geographical Offender Profiling Map

Key

1 Red = The Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

2 Magenta = Second Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

3 Green = Third Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

4 Blue = Fourth Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

5 Cyan = Fifth Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

6 Yellow = Sixth Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

7 Aqua = Seventh Most Probable Search Area where the Offender's Home Will Be Found

The relevant theories underlying geographic profiling, as they apply to offender profiling are now discussed.

Routine Activity Theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979).

‘Routine Activity Theory (R.A.T.)’ proposes that for a crime to occur there are three necessary components, which must converge in time and space:

the presence of a likely offender (an individual who is motivated to commit a crime);

a suitable target (e.g. something valuable and accessible); and

the absence of a capable guardian (e.g. security guard, policeman, citizen).

The movement of people throughout their daily routine activities generates such convergences, and thus influences the likelihood and risk of crime over time. The approach focuses on the discovery of “opportunities” in the form of victims and targets during non-criminal activities.

Crime Pattern Theory (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981).

Brantingham & Brantingham drew heavily from R.A.T. to propose that individuals develop an awareness of space; an area of familiarity, during their day-to-day activities, and that this governs the geographic patterning of their criminal and non-criminal behaviour. Awareness spaces include nodes (the places that people travel to and from, e.g. home, work or friend’s house), paths (the routes between the nodes) and edges (the boundaries of the region of familiarity).

Rational Choice Theory (Cornish & Clarke, 1986)

Rational Choice Theory’ proposes that the decision to offend is purposeful and rational, and is made by weighing up the pros or gains (e.g. personal, financial) associated with a crime against the cons or costs (e.g. the risks involved). These decisions are governed by environmental cues, and the rational consideration of the efforts, rewards and costs associated with potential crime locations. Lundrigan & Canter (2001a) assert models of rational choice are concerned with offences such as burglary and robbery, which are instrumental. Lundrigan & Canter (2001a) also state that the rational choice explanation of spatial behaviour involves the making of decisions and choices which exhibit a trade-off between increased opportunity and greater reward the further an offender travels from home, as well as the cost of time and effort and risk. The benefits of a criminal action are the net rewards of crime and include not only material rewards but also intangible benefit such as emotional satisfaction. The costs or risks of crime are those associated with formal punishment should the offender be apprehended. Lundrigan & Canter (2001a) note the concept of limited rationality best explains spatial behaviour of offenders. Offenders do not consider all the relevant factors every time an offence is considered, other influences (moods, motives, perceptions of opportunity, alcohol, and their appetite for risk) apparently unconnected to the decision at hand take over. Offenders are, therefore, behaving rationally as they see at the time. What is considered rational may change over time.

Propinquity and Morphology

Canter, Hammond, Youngs, & Juszezak (2012) say there are two fundamental aspects of offenders’ geographical activities that allow inferences of their most likely home base or location to be inferred from mapping the locations of their offences. The first is propinquity, which is the tendency for the probability of the crime locations to reduce incrementally as the distance from the offender’s home/base increases, often depicted as an aggregate decay function. The other factor is morphology; this is the tendency for offences to be distributed around the offender’s home or base. Morphology relates to structure whereas propinquity relates to closeness. Propinquity deals with the proximity of crime locations to the main places in the offender’s life, notably his/her home, or base.

The Circle Hypothesis

The Circle Hypothesis builds on the idea of there being a simple starting point and to see if the offender would have a base within this area. It is not always clear how large the circle is, and it does not always follow that the offender has a base at the centre of the circle. However, the circle hypotheses is a predictor of the home location. Outliers have a significant impact on the size of the circle. The home base is typically where the individual sleeps, but this ultimately depends on the type of offender. Circle theory proposes that geographical profiling and individual offender profiling behaviour assumes that an offender’s home base will be central to their crimes.

Canter & Gregory (1994) found that individuals tend to offend close to locations in which they live. Offenders when travelling around their home area find places where crimes can be committed. Brantingham & Brantingham (1981) argue that the concentration of criminal activity around the home is influenced by biased information flows. More information will be available at locations close to the home base it is, therefore, more probable that offenders will be aware of criminal opportunities in these areas.

Brantingham & Brantingham (1981) contend that the security of the offender’s home range and the familiarity of the area outweighs the risk of recognition in regions that are not in the immediate area of the offender’s home base. Familiarity is thus a determining factor of where criminals will commit crimes. There are both maximum and minimum distances from an offender’s home/base to the area in which they offend. According to Canter & Gregory (1994), the literature supports the idea that a criminal forms a mental map of his home range. This mental map probably influences criminal and non-criminal spatial activity of offenders.

Criminals tend not to travel far to commit the first offence; a ‘buffer zone’ exists around the offender’s home where the offender is unlikely to engage in criminal acts because of the risk of identification (Brantingham & Brantingham,1981; Canter & Larkin,1993). Fritzon (2001) argues that the spatial behaviour of burglars is more random because essentially opportunity to commit burglary exists everywhere. The location of their crime site, therefore, might be expected to be more dependent on concerns about detection or opportunistic factors such as coming across a house which is unoccupied and does not present environmental or psychological obstacles against being burgled.

Canter and Larkin (1993) found that the home was a location within the crime circle and is likely to be close to the centre of that circle. The average distance of offences to home for offenders studied by Canter and Larkin (1993) was 1.53 miles. Criminals typically travel further away from home at some stages of their offending careers.

Canter and Larkin found that the diameter of the circle was the distance between the two furthermost crimes to define the area found in most the cases the offender lived in the area circumscribed by their crimes. The circle consists of the smallest area incorporating all the crimes. This research has been extended so that a prediction of the offender home location can be derived from any given series by:

defining the criminal range for that series using the smallest possible circle that encapsulates all the crime locations; and

treating the centre of that circle as the most probable location for the offender’s residence.

Marauders and commuters.

Commuters commit crime around an area that they have some familiarity with but this is well away from their home location. Marauders commit crimes that are more spread out. The assumptions underlying the marauderer model are:

the opportunity for crimes is evenly distributed;

the offender does have a base within the area of the crimes;

the tendency to put distance between adjacent offences;

offender feels vulnerable in the area of previous offences; and

no very precise targeting.

The Consistency Hypothesis.

The consistency hypothesis posits that criminals will carry out similar level crimes. They are more likely to live near the centre of the crime because they are more likely to know the area quite well and, therefore, there are more crimes committed in the area. The Spatial Consistency Hypothesis is that offenders will only commit an offence in an area that they know.

References and Recommendations for Further Reading

Bennell, C. Snook, B., Taylor, P. J., Corey., S. Keyton, J (2007) It’s no riddle choose the middle: effect of number of crimes and topographical detail on police officer predications of serial burglars’ home locations. Criminal Justice Behaviour. 34(1) 119 – 132

Bennett T., & Wright, R. (1984) Burglars on burglary: prevention and the offender. Aldershot, Hants: Gower

Block, R. & Bernasco,W. Finding a serial burglar’s home using distance decay and origin destination patterns: a test of empirical Bayes journey-to-crime estimation in the Hague. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 6(3) 187 – 211

Brantingham, P. J. and Brantingham, P. L (1981) Notes on the geometry of crime. In: Environmental Criminology, Edited by Brantingham P.J and Brantingham P. L. Beverley Hills: Sage; 27 - 54.

Canter, D. V. (1977) The Psychology of Place. London: Architectural Press.

Canter, D. V. (2007) Mapping murder: the secrets of geographical profiling. London: Virgin

Canter, D. V, & Gregory, A. (1994). Identifying the residential location of rapists. Journal of the Forensic Society, 34(3), 169-175. doi: 1016/S0015-7368(94) 72910-8

Canter, D. V. Hammond, L., Youngs, D. E, & Juszczak, P (2013). The efficacy of ideographic models for geographical offender profiling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 29, 423 – 446.

Canter, D. V., & Larkin, P. (1993). The environmental range of serial rapists. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13, 63– 69

Canter, D. V. & Youngs, D. E. (2009). Investigative Psychology: offender profiling and the analysis of criminal action. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review. 44(4) 588 – 608

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (1986). The Reasoning Criminal: rational choice perspectives on offending. New York: Springer

Fritzon, K. (2010). An examination of the relationship between distance travelled and motivational aspects of firesetting behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(1), 45 – 60 doi. 10.1006/jevp.2000.0197

Lundrigan, S., & Canter, D. V. (2001a). A multivariate analysis of serial murderer’s disposal site location choice. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 423 – 432.

Lundrigan, S., & Canter, D. V. (2001b). Spatial patterns of serial murder: an analysis of disposal site location choice. Behavioural Sciences and the Law, 19, 595 – 610. doi:10.1002/bsl.431.

Paulsen, D. (2006). Human vs machine: a comparison of the accuracy of geographic profiling methods. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 3(2) 77 – 89

Snook, B. Canter, D. V., & Bennell, C (2002). Predicting the home location of serial offenders: a preliminary comparison of the accuracy of human judges with a geographic profiling system. Behavioural Sciences and the Law. 20, 109 – 118

Find Out More About Offender Profiling

- Offender Profiling

- Offender Profiling and Crime Analysis

- Offender Profiling a Review and Critique of Approaches

Mental Health Law

Mental Health and the Law

There is a strong relationship between mental health and the law, as far as the rights of people with mental illness is concerned the World Health Organisation outline 10 basic principles that should protect the rights of people with mental illness:

Mental Health Care Law: 10 Basic Principles - World Health Organisation

- The promotion of mental health and prevention of mental disorders.

- Access to basic mental health care.

- Mental health assessments in accordance with internationally accepted principles.

- Provision of the least restrictive type of mental health care

- Self-determination

- Right to be assisted in the exercise of self-determination

- Availability of review procedure

- Automatic periodical review mechanism

- There must be a qualified decision-maker to detain the person

- Respect for the rule of law.

Psychology and the Law

Expert Psychologists who work with individuals who have mental illnesses frequently have two provide expert opinion for the prosecution and defence in criminal cases.

Mental health law includes areas such as the insanity plea, fitness to stand trial and testamentary capacity. Mental health law is also concerned with establishing mens rea and culpability, and compulsory detention.

The intersection between mental health and the law is further developing in the area of forensic evaluation of children and adolescents in child custody, its application to delinquency, maltreatment, personal injury and court-ordered evaluations.

The Mental Health Act 1983

How is Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983 Used?

Section 2 of the Mental Health Act provides the ability of mental health professionals to detain and treat people under the Mental Health Act When they are too unwell to care for or make decisions for themselves. The purpose of Section 2 is to ask the patient to come into the hospital for an assessment to determine whether they have a severe end enduring mental illness. Their detention is in the interest of their own health and safety or the protection of other people. Admission under Section 2 normally lasts for 28 days.

How is Section 3 of the Mental Health Act 1983 Used?

A Section 3 of the Mental Health Act is commonly known as a Treatment Order. This means the patient is compulsorily treated in hospital when certain conditions are met. These are that the individual is suffering from a mental disorder which is of such a degree that warrants the person being compulsorily detained in hospital. There must be a risk to the person or other people. The other conditions are, the treatment cannot be given without the Section 3 being in place, and there must be appropriate treatment available. Detention under Section 3 of the MHA can last up to 6 months.

What Does it Mean to be Sectioned Under the Mental Health Act?

ASD Assessment

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

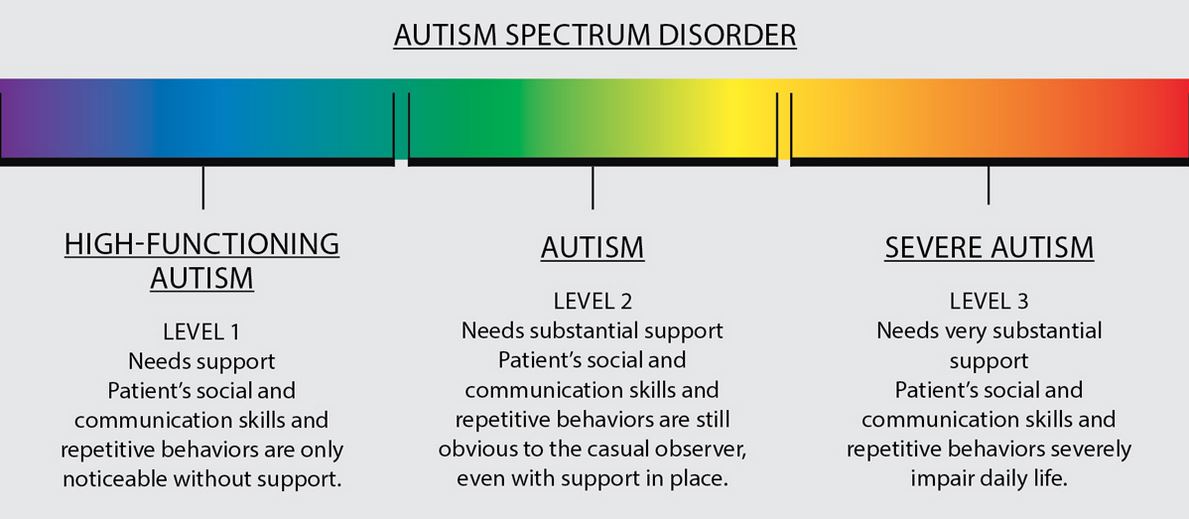

People with autism exhibit the severity of autistic symptoms on a spectrum. The lowest level of the autism spectrum is Level 1 (high functioning autism sometimes called Asperger Syndrome). At the opposite end of the spectrum are individuals at Level 3, these individuals require substantial support.

Figure 1: Autism Spectrum

Autism Symptoms

ASD Assessment

The symptoms of autism displayed may vary according to age, intelligence and whether the individual can speak or not. The key characteristics in the ASD assessment process are summarised below using the framework developed in the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Second Edition). This framework is closely aligned to the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (Fifth Edition) (DSM-5).

Please note that autism can often cooccur with other conditions such as ADHD, dyspraxia, dyslexia, learning disabilities and anxiety.

A. Autistic Language and Communication

Speech Abnormalities

Some people with ASD have speech that has little variation in pitch and tone, rather flat or exaggerated intonation. Sometimes it can be speech that is somewhat unusual or slow or jerky. At the opposite end of the spectrum are individuals with phase speech which is inadequate in complexity or frequency. Some individuals with autism do not speak at all.

Repetition

My individuals with ASD show immediate repetition of the last statement or series of statements given by others.

Stereotyped/Idiosyncratic Use of Words or Phrases

People with ASD range from those who use words or phrases which tend to be more repetitive than most. At the other end of the spectrum are individuals who occasionally use stereotyped words.

Conversation

Individuals with ASD range from those who speech include some spontaneous elaboration of responses to those with little spontaneous communicative speech.

Pointing

Some people with autism use pointing to reference objects and express interest, they do so without coordinated gaze or vocalisation.

Descriptive Gestures

Many individuals with autism use some descriptive gestures to represent an event such as brushing one’s teeth or combing one’s hair. Others use very limited conventional or descriptive gestures.

Offers Information

An individual with ASD may spontaneously offer information at one end of the spectrum. At the other end of the ASD spectrum, an individual may rarely offer information except about their circumscribed interests.

Asks for Information

At one end of the ASD spectrum, individuals may occasionally ask for information. At the other end, the individual will rarely or never ask others about feelings or experiences.

Reports Events

Some people with autism can report specific nonroutine events. At the opposite end of the spectrum, some individuals provide inconsistent or insufficient responses to even specific probes.

Conversation

Individuals vary from those who can engage in dialogue to those who have little spontaneous communicative speech.

Descriptive Gestures

At one extreme some individuals make spontaneous use of several descriptive gestures. At the other end, there is very limited spontaneous use of conventional, instrumental, informal or descriptive gestures.

Emphatic or Emotional Gestures

There is a spectrum of abilities with some people able to show a variety of appropriate and emphatic and emotional gestures that are integrated to speech. At the other end of the spectrum, there are those that show no or a very limited emphatic or emotional gestures.

AUTISM SPECTURM DISORDER

B. Reciprocal Social Interaction

Some Individuals Display Poor Eye Contact

Some individuals with ASD display poor eye contact to modulate or terminate social interactions.

Ability to Direct Facial Expressions Appropriately

Some individuals with autism do not direct their facial expressions to other people when communicating appropriately.

Ability to Show Pleasure and Shared Enjoyment and Interaction

Some individuals with ASD can show pleasure during more than one activity. Some people with autism may have little or no expressed pleasure in interactions.

Ability to Communicate Own Effect

Although some autistic individuals can communicate a range of emotions, others have hardly any or no communication of what they are feeling or have felt.

Ability to Link Speech to Non-Verbal Communication

At one end of the spectrum, individuals moderate their non-verbal gestures in line with their speech. At the other end of the spectrum there is some avoidance of eye contact, or in extreme cases, individuals are unable to speak or make minimal or no use of gesture and facial expression.

Ability to Communicate Feelings and Emotions Using Words

While some individuals are able to communicate many emotions, the feelings they have felt ―others exhibit hardly any ability to communicate the feelings and emotions verbally and nonverbally.

Ability to Understand of The Emotions of Others and Show Empathy to Others

Although many individuals with autism can understand and label or respond to the emotions of others; some individuals have no or minimal ability to identify, communicate and understand the emotions of others.

Ability to Show Insight into Social Situations and Relationships

Some individuals with autism show no or limited insight into typical social relationships. At the other end of the autistic spectrum, some individuals show insight into the nature of many typical social relationships.

Ability to Show Responsibility for His or Her Own Actions

At one end of the autistic spectrum are individuals who are responsible for many of their own actions across a variety of contacts which include daily living, work school and money et cetera. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who have a restricted sense of responsibility for their actions as would the appropriate to their level of development and age.

Quality of Attempts to Initiate Social Interaction

At one end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who use verbal and non-verbal methods to communicate social overtures appropriately. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who cannot engage in social overtures of any kind.

Frequency of Attempts to Get an Maintain Attention of Others

Although some individuals make frequent attempts to maintain the attention of others and direct their attention, others show an unusually frequent or excessive demand for attention.

Quality of Social Responses

While some individuals display a diversity of appropriate responses that change according to the immediate situation. However, others have minimal or inappropriate responses to the social context.

Frequency of Reciprocal Social Communication

Autistic individuals vary from those who make extensive use of verbal or non-verbal behaviours for social interchange to those that engage in little or no communication.

C. Imagination

Imagination/Creativity

Some individuals with autism show no creative or inventive actions. At the other end of the ASD spectrum are individuals who display numerous creative, spontaneous responses in activities and communication.

D. Stereotyped Behaviours and Restricted Interests

Unusual Sensory Interest in Play Material

Some individuals with ASD exhibit a pronounced unusual sensory interest while others show no unusual sensory interests or sensory seeking behaviours.

Hand to Finger and Other Complex Mechanisms

Some individuals with ASD display no hand to finger or other complex mechanisms such as repetitive clapping. At the other end of the spectrum, there are individuals who frequently exhibit such behaviours.

Self-injury

Some individuals with ASD engage in aggressive acts to harm themselves, these acts include headbanging, pulling out their own hair, biting themselves or slapping their own faces. Other individuals with ASD do not engage in this type of behaviour.

Disproportionate Interest or Reference to Specific Topics or Repetitive Behaviours [h3]

Some individuals with ASD display a marked preoccupation with interests or behaviours which interfere with their day-to-day activities. For example, a type of car. Other individuals with ASD display no excessive interests.

Rituals and Compulsions

Some individuals show obvious activities or verbal routines which must be discharged in full or in line with a sequence which is not part of a task. However, others may have one or several activities or routines which they have to complete in a specific way. They will become anxious if this activity is disrupted.

Other Abnormal Behaviours

Although some individuals can sit still appropriately, other individuals with ASD may have difficulty sitting still and may be overactive. Some individuals with autism, however, may be underactive.

Autism Meltdowns, Aggression and Disruption

Many people with autism display no destructive or aggressive behaviour. However, some people with ASD may talk loudly, they may have significant temper tantrums. Such tantrums frequently occur when there is a change of routine or change of environment.

Anxiety

Whilst many individuals with ASD show no marked signs of anxiety, others show significant anxiety in their day-to-day interaction.

ASD CHECKLIST - HOW MUCH DO YOU REALLY KNOW ABOUT AUTISM?

Find Out More About Autism

NHS Choices – Autism Spectrum Disorder

What is Autism?

What is Autism? Scottish Autism

Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome

Everything You Need to Know About Autism

Autism

Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment

Autism and The Law

People with ASD in the criminal justice system are affected as victims, witnesses and defendants. It is important that defendants with ASD are not unnecessarily criminalised because of their condition. The Youth Justice Centre (2018) recommend that it is important that both victims and defendants are supported to give best evidence at the police station and at court.

Because many people with autism are often quite vulnerable, there is a need for prosecutors to draw this to the attention of judges when sentencing perpetrators of crimes against victims with ASD.

Autism and Criminal Defence

Some individuals with autism may find it difficult to answer even the most straightforward questions asked by the police. Additionally, some young children with autism who self-harm may unwittingly be assumed to be victims of child abuse.

A person with autism might:

- Be overwhelmed by police presence;

- Fear a person in uniform;

- React with fight or flight;

- Not respond to “stop” or other commands; and

- Not respond with his or her name or other verbal commands

- May avoid eye contact.

Mogavero (2016) found that too many individuals with ASD are enter the criminal justice system due to inappropriate sexual behaviour.

Judges have discretion when sentencing, and it is important to point out that a custodial sentence may have a more devastating effect for an individual with autism than someone without the condition.

AUTISM AND CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY

LEARN MORE ABOUT AUTISM AND THE LAW

Autism and the Criminal Justice System

Autism Information for Law Enforcement

Autism and the Criminal Justice System

Autism and Oughtisms

Autism – Youth Justice Legal Centre

Autism, Sexual Offending, and the Criminal Justice System

Autism and Offending Behaviour: Needs and Services

Understanding offenders with autism-spectrum disorders: what can forensic services do?: Commentary on…..Asperger Syndrome and Criminal Behaviour

Autism and Disability Discrimination

Autism and Child Contact

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)

Pathological Demand Avoidance in Adults

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

People with Pathological Demand Avoidance or PDA are driven to avoid demands due to their high anxiety levels when they feel that they are not in control.

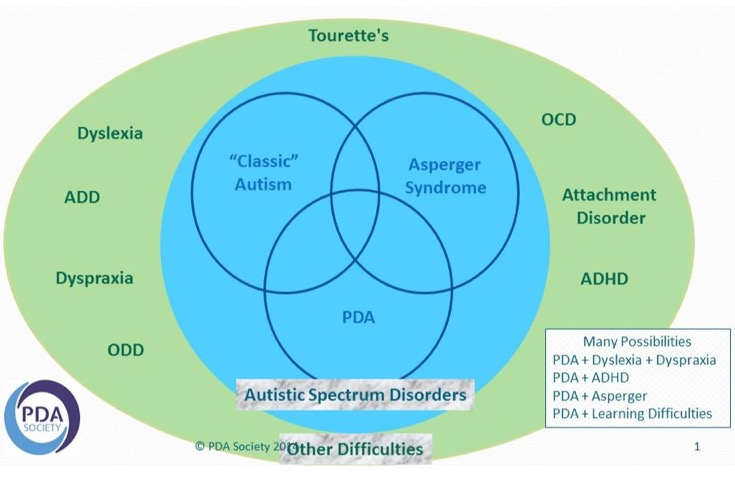

PDA is increasingly recognised as being part of the autism spectrum. Some psychologists refer to it as a diagnostic profile or sub-type within autism. Individuals with PDA share difficulties with others on the autism spectrum in terms of social aspects of interaction and communication, together with some repetitive behaviour patterns. However, people with PDA often seem to have better social understanding than others on the spectrum

In individuals with PDA, their avoidance is clinically-significant in its extent and extreme nature. Children and adults with PDA can also mask their difficulties, and their behaviour can vary between settings.

PDA is a relatively new diagnosis it is frequently confused with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) as a diagnosis. PDA as shown in the diagram below from the PDA Society (www.pdasociety.org.uk) PDA falls within the circle of Autistic Spectrum Disorders, whereas ODD does not. There other conditions with frequently cooccur with autism in the green circle.

Figure 1: Pathological Demand Avoidance and its Interplay with Autism

Please note that Asperger Syndrome is now referred to as High Functioning Autism (HFA), although there is still some dispute that they are separate conditions.

There is overlap between most of these diagnoses. The term 'can't help won't' is often used to describe PDA.

PDA Not Yet Recognised in the DSM-5 and ICD-10

Many people are diagnosed with PDA as a condition in its own right. Presumably, this is because they do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum disorder ASD. The problem with this approach is that:▪ PDA is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - fifth edition (DSM-5)

▪ PDA is not included in the International Classification of Diseases - 10th Edition (ICD-10)

Consequently, if the condition does not appear in the leading diagnostic manuals for psychological conditions some schools and educational institutions may find it difficult to provide support. Many argue that every individual with PDA is autistic.

PDA as a Form of Autism Spectrum Disorder

It is becoming more common for people to receive a diagnosis of ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) characterised by extreme demand avoidance.’ Alternatives ways of putting the diagnosis are:

ASD with a PDA profile;

ASD sub-type PDA; or

Atypical autism with demand avoidant tendencies.

Learn more about the key Characteristics of Pathological Demand Avoidance

6 Main Characteristics Pathological Demand Avoidance Are:

Resisting and avoiding the ordinary demands of life;

Using social strategies as part of the avoidance;

Appearing sociable on the surface but lacking depth in their understanding;

Excessive mood swings and impulsivity;

Being comfortable in role play and pretence, sometimes to an extreme extent and often in a controlling fashion; and

Obsessive’ behaviour that is often focused on other people, which can make relationships very tricky.

Individuals with PDA have Many Positive Characteristics

One should not lose sight of the fact that individuals with PDA can be quite positive and have many strengths. They can interact well socially and can be quite talkative. They are said to have charm and can be warm and affectionate. Their need to take control means that they are often seen as quite determined. They can have a rich imagination and are frequently described as creative and passionate.

8 Top Tips on How to Support Individuals with Pathological Demand Avoidance

Pathological Demand Avoidance Treatment

1. Flexibility

Always make sure that your day activities are flexible, the the individual with PDA child might not want to do them in a particular order they might want to do it in a completely different order. Allow that flexibility and you will find that the individual with PDA will be able to cope with the anxieties of the day a lot easier.

2. Control.

People with PDA need to feel so they are in control like autism, and other ASDs anxiety rules the day for them if they do not feel in control of a situation the sense of anxiety rises and then they feel panicky and fearsome of what is going to happen; particularly when it comes to change for PDA individual the fear of not being in control generates a resistance to what if the change or a request you might want them to do something they might not be able to do or not want to do it because they might get it wrong.

3. Ease Anxiety.

If changes needed, then talk the PDA individual through it you might want to talk to them you might want to write it down in steps like bullet points or you could use images or pictures either way show the PDA individual that there is a beginning a middle and the end of a request or activity you want them to carry out; this will ease the anxiety for the individual

4. Unravel the Fear

PDA individuals often see the worst in every situation they will always think of the worst thing that could possibly happen; reassure the PDA individual that there is nothing to worry about - do not be confrontational.

5. Building up Self Confidence

A lot of PDA individuals have a problem with self-esteem and confidence they think that if they do whatever it is they are being asked to do they are not going to do it properly; it might be that they feel they will be laughed at. They might feel embarrassed. There is a huge amount of anxiety that is behind these inner fears the best thing to do is boost up PDA individual’s confidence tell them exactly what they get right, tell them what they are good at.

6. Make the change outcome beneficial

Help the person with PDA see that the change out is beneficial to them, and not to you. The key here is to make them feel that they are making the decision themselves, make them think that actually the decision is their decision. Always make the outcome look beneficial to them and not to you.

7. Provide a Responsibility

We know that people with PDA love to be in control of their own world given the responsibility to do something to help themselves this will make them feel as though they are completely in control of their being and their body and, therefore, the outcome. The secret to it is careful wording in the request do not bark an order at them but suggest a way of doing something and add the element of responsibility into that request so they feel as though they are doing something for themselves.

8. Set boundaries

People with PDA need to know there will be a beginning a middle and an end. Help them to think what it will be like to achieve the end result. Provide them with a sense of responsibility.

Learn More About Pathological Avoidance Syndrome

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

Pathological Demand Avoidance

Pathological Demand Avoidance – One Family's Story

Pathological Demand Avoidance: Behavioural Strategies

What is a Child Psychologist?

Educational Psychologist Assessment

It is a common misconception that only educational psychologists can assess specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia, ADHD, dyspraxia, and autism. However, psychologists from several other disciplines in psychology frequently assess these conditions and the learning needs of children and adults.

Educational Psychologists and Child Psychologists Assess Dyslexia, Autism, ADHD, Learning Disabilities & Children's Emotional Problems

Child Psychologist Near Me

The term child psychologist, in the UK, means a psychologist who spends at least 30% of their time carrying out assessments and therapy with children and young people.

Child psychologists are primarily concerned with developmental psychology, special educational needs, learning disability, the impacts of child abuse and parenting practices. Child psychologists may work on the same psychological issues as educational psychologists.

Find A Child Psychologist Near Me: London + Birmingham + Nottingham

Other Psychologists who Assess Learning Disabilities and Neurodevelopmental Conditons

Psychologists working in other areas of psychology such as neuropsychology, frequently assess neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, and ADHD, Developmental Coordination Disorder (dyspraxia), learning disabilities and specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia and dyscalculia.

Occupational psychologists, depending on their experience, may carry out assessments of dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia ADHD, autism and learning disability in an occupational setting. Similarly, some clinical psychologists and forensic psychologists frequently carry out assessments of these conditions.

What is an Educational Psychologist?

Educational Psychologist

Training to Become an Educational Psychologist

What is their Role - Educational Psychologists

What is A Child Psychologist?

Starting a Career as a Child Psychologist

When to see a Child Psychologist

What Are the Responsibilities & Duties of a Child Psychologist?

How Child Psychologists Help

Stopping Children Self-Harming

What to Do When Your Child is Being Bullied

Why Your Child Should Get a Part-time Job

Child Psychology: How to Discipline a Child the Does not Listen

Learning Disablity

Learning Disabled and Intellectually Gifted Under 5-Year Olds

We have reviewed two IQ tests the Stanford-Binet and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence that we use to assess intellectually gifted and learning disabled under five-year olds. The problem for psychologists carrying out assessment is that there are limited psychological tests available to assess under five-year olds. Furthermore, children under five develop intellectual ability at very different rates.

The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale

The benefit of using the Stanford-Binet IQ test is that it can assess individual from the age two up to 85 years plus.

Thus, the Standford-Binet is more cost effective for psychologists that both in terms of time it takes to learn to administer the test and the cost of materials than the market leading IQ test the Wechsler Intelligence Scales. The Wechsler Scales have three different IQ test for each age group, preschool children, children from five to 16 and adults from 16 upwards, it costs considerably more.

Learn How to Answer the Stanford Binet Intelligence Test

Practice Standford Binet IQ Test Questions

The main limitations of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence test are in the UK is that many of the tests that are used to provide additional information on learning disabled and intellectually gifted and learning disabled under 5 year olds use the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. Finally, the Stanford-Binet is not yet approved as one of the intelligence tests for the identification dyslexia.

Dyslexia & Equality

The Interplay Between the Disabilities of Dyslexia, Dyspraxia and ADHD

Dyslexia can co-occur with other neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD. Because individuals are born with dyslexia, ADHD other conditions such as autism these conditions often meet the criteria of a disability under the Equality Act 2010.

That is, they are:

- Significant

- Substantial; and

- Have a long-term effect on the individual’s normal day to day activities.

Extra Time In Examinations and Additional Support

The implications for of this in the for school, college and university students is that these students have special educational needs. They should be entitled to extra time to complete examination, additional tuition and other reasonable adjustments to the way that they are taught. For those in university are entitled to a grant from Student Finance England – to purchase the additional equipment and tuition they need.

Many Dyslexics Are Highly Intelligent Achievers

A common misconception is that people with dyslexia are less intelligent – this is incorrect there are many highly intelligent individuals and high achievers with dyslexia in all walks of life such including Doctors, lawyers and famous businss people such as Richard Branson. Those with dyslexia, and dyspraxia and have a more diverse way of processing information.The Psychologist as an Expert Witness

Advanced Assessments Sitemap

Press This Image

Open Now - 24 hour Service - Open Weekends

We work throughout the UK

UK: +44 (0) 208 200 0078 Emergencies: +44 (0) 7071 200 344

180 Piccadilly, London, W1J 9HF

Please do not attend our office if you do not have an appointment

Twitter: @ExpertWitness_

Google Plus

Facebook

We are a part of the Strategic Enterprise Group